Why Scotland wastes what England rations

The wettest nation in Europe engineered its own water crisis through institutional design

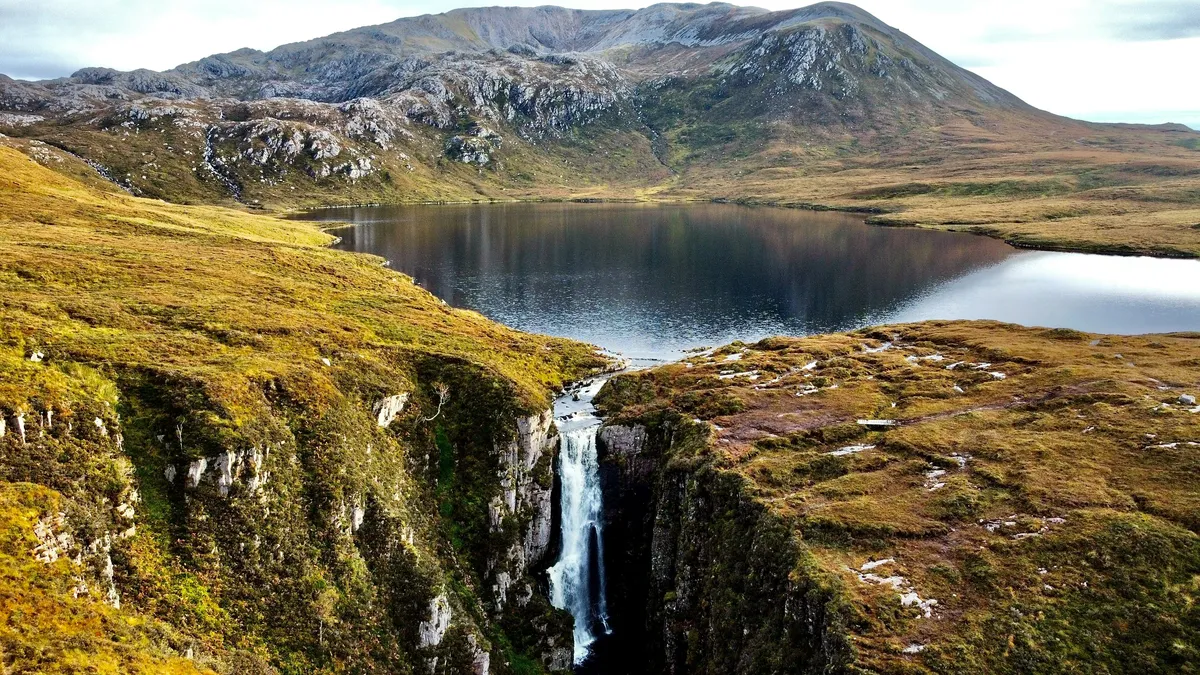

The wettest nation in Europe has engineered a water crisis through institutional design. Scotland consumes 40% more water per person than its resource-scarce neighbours, not despite its abundance but because of it. While England rations water through meters and pricing signals, Scotland's flat-rate system has created perverse incentives that reward waste just as climate change threatens the very abundance that enabled such dysfunction.

The numbers expose systematic dysfunction rather than resource shortage. Scots use 178 litres of water daily compared to 140.4 litres in England and Wales—a 40% differential that reveals institutional failure. More diagnostically significant: English households with water meters consume just 126.6 litres daily whilst non-metered households use 175.3 litres, nearly identical to Scottish patterns. This natural experiment demonstrates precisely what happens when payment systems divorce consumption from cost awareness.

This abundance dysfunction operates through a deceptively simple mechanism that would make behavioral economists wince. Scottish households pay for water through council tax bands rather than usage meters, severing the fundamental connection between consumption and cost that regulates behavior in functioning markets. Scottish Water CEO Alex Plant diagnosed this institutional blindness with clinical precision: "We assume it's abundant and therefore we don't worry about it too much."

The result is systematic market failure. High-consumption households receive implicit subsidies from conservation-minded neighbors through the council tax system. A family using 300 litres daily pays the same water contribution as neighbors using 100 litres, provided they live in similar properties. This cross-subsidy mechanism doesn't just fail to discourage waste—it actively punishes efficiency whilst rewarding excess.

Diagnosing the payment pathology

This abundance trap mirrors patterns documented globally in resource economics. The "resource curse" typically describes how oil-rich nations like Nigeria or Venezuela squander natural wealth through poor governance, but the same dynamics operate in water systems. Abundance breeds institutional complacency, reducing pressure for efficiency improvements that resource-scarce regions develop by necessity.

Norway escaped petroleum resource curse through sovereign wealth funds and diversified institutions. Botswana avoided diamond curse through transparent governance. Both succeeded by creating scarcity pricing even amid plenty—exactly what Scotland's water system lacks.

The behavioral economics are straightforward. Usage-based pricing triggers what economists call "marginal utility per dollar" optimisation—customers naturally reduce consumption when they see direct cost relationships. Research consistently shows 20-30% consumption reductions when households switch from flat-rate to metered billing, regardless of cultural context.

Scottish households, insulated from consumption costs, lack feedback loops that would moderate usage. High-consumption households receive implicit subsidies from conservation-minded neighbors through the council tax system, creating cross-subsidies that punish efficiency whilst rewarding excess.

When abundance meets scarcity

Climate reality is dismantling Scotland's abundance assumptions with methodical efficiency. The country recorded its second sunniest April since 1910, whilst groundwater levels in Fife and Angus crashed to record lows. The Scottish Environment Protection Agency confirmed that Loch Ness—containing more freshwater than all English and Welsh lakes combined—dropped to five-year lows during recent dry weather.

These aren't statistical anomalies but systematic shifts. Climate models predict 10-20% reductions in summer rainfall alongside doubled frequency of low river flow events by 2050. The infrastructure designed for Scotland's legendary precipitation faces stress patterns it was never engineered to handle.

Yet domestic consumption continues climbing. Water use increased 8% between 2002-2014 even as business consumption fell 21%, suggesting that pricing signals work perfectly for companies facing direct costs but fail completely for households insulated by flat-rate systems. The divergence exposes institutional architecture unprepared for resource constraints.

The whisky industry, fundamental to Scottish exports, requires 296 litres of cooling water per litre produced across 134 operating distilleries. Soft fruit production demands intensive irrigation during precisely the dry periods when water stress peaks. These economic pressures intensify as climate patterns shift, yet household consumption—representing the largest water use category—faces no pricing constraints that would encourage systematic efficiency improvements.

Infrastructure stress under climate pressure

Scottish Water faces impossible demands: maintain universal service whilst managing increasing consumption and decreasing supply reliability. The agency supplies 1.34 billion litres daily through 60,000 miles of aging pipes designed for different usage patterns.

Higher consumption increases system pressure, accelerating leakage in infrastructure networks. Surge capacity for climate-driven demand spikes doesn't exist. The system optimised for abundance struggles with scarcity management.

Revenue certainty through council tax contributions eliminates institutional pressure for demand management. Scottish Water succeeds financially regardless of conservation outcomes, reducing organisational urgency for efficiency programs that would threaten revenue streams.

Organisational resistance to price signals

Change requires confronting entrenched interests. Affluent households consuming more water pay higher council tax but receive cheaper per-litre rates—a regressive subsidy they're unlikely to surrender voluntarily. Politicians avoid unpopular metering discussions that might increase bills for visible constituents.

Scottish Water's pilot project installing "smart monitors" in 2,000 Dundee homes represents cautious progress. These devices show usage without changing payment systems—information without incentives. CEO Plant emphasises they're "monitors rather than meters because you're not going to pay for it," revealing institutional reluctance to implement pricing reforms.

This halfway measure might increase conservation awareness but won't create systematic behavioral change that direct pricing achieves. The fundamental problem—disconnected payment systems—remains unaddressed.

Institutional reform or climate reckoning

Scotland confronts a diagnostic choice that reveals deeper truths about resource management under climate uncertainty. The country can reform pricing systems whilst abundance provides political cover for gradual adjustment, or wait for scarcity to force institutional changes through crisis management.

The former path preserves choice and enables systematic adaptation. Scottish Water's tentative Dundee pilot—installing "monitors rather than meters because you're not going to pay for it"—represents institutional reluctance to implement reforms that would threaten revenue certainty. This halfway approach might increase conservation awareness but cannot create the behavioral changes that direct pricing achieves systematically.

Other regions developed water efficiency through necessity rather than choice. Scotland's abundance prevented this institutional evolution, leaving it paradoxically vulnerable when constraints finally arrive. The challenge isn't technical but institutional: designing incentive systems that reward conservation even when abundance tempts waste.

Climate change operates on timescales that don't accommodate institutional learning curves. Scotland's abundance trap demands resolution before external pressures make reform infinitely more complex and politically fraught. The diagnosis is clear; the prescription requires political courage that abundance has historically discouraged.